Many of the statistical approaches used to assess the role of chance in epidemiologic measurements are based on either the direct application of a probability distribution (e.g. exact methods) or on approximations to exact methods. R makes it easy to work with probability distributions.

Rbinom(n=10, size=20, prob=.4) 1 8 7 6 6 5 5 10 5 8 11 might return. Bootstrapping is type of sampling where the underlying probability distribution is either unknown or intractable. You can think of it as a way to assess the role fo chance when there is no simple answer. Lecture Notes - All content during semester including all areas of the body. Revision Notes, Human Health & Disease Concepts, 1,2,3,5,7 Week. R script (1) The usual Rstudio screen has four windows: 1. Workspace and history. Files, plots, packages and help. The R script(s) and data view. The numbers of degrees of freedom are pmin (num1,num2)-1. So the p values can be found using the following R command: pt (t, df =pmin( num1, num2)-1) 1 0.01881168 0.00642689 0.99999998. If you enter all of these commands into R you should have noticed that the last p value is not correct. Lapply returns a list of the same length as X, each element of which is the result of applying FUN to the corresponding element of X. Sapply is a user-friendly version and wrapper of lapply by default returning a vector, matrix or, if simplify = 'array', an array if appropriate, by applying simplify2array.

probability distributions in R

Base R comes with a number of popular (for some of us) probability distributions.

| Distribution | Function(arguments) | |

|---|---|---|

| beta | - | beta(shape1, shape2, ncp) |

| binomial | - | binom(size, prob) |

| chi-squared | - | chisq(df, ncp) |

| exponential | - | exp(rate) |

| gamma | - | gamma(shape, scale) |

| logistic | - | logis(location, scale) |

| normal | - | norm(mean, sd) |

| Poisson | - | pois(lambda) |

| Student's t | - | t(df, ncp) |

| uniform | - | unif(min, max) |

Placing a prefix for the distribution function changes it's behavior in the following ways:

dxxx(x,) returns the density or the value on the y-axis of a probability distribution for a discrete value of x

pxxx(q,) returns the cumulative density function (CDF) or the area under the curve to the left of an x value on a probability distribution curve

qxxx(p,) returns the quantile value, i.e. the standardized z value for x

rxxx(n,) returns a random simulation of size n

So, for example, if you wanted the values for the upper and lower limits of a 95% confidence interval, you could write:

Recalling that the standard normal distribution is centered at zero, and a little algebra, can help you return a single value for a confidence limit.

exact vs. approximate methods

These approximations were developed when computing was costly (or non-existent) to avoid the exhaustive calculations involved in some exact methods. Perhaps the most common approximations involve the normal distribution, and they are usually quite good, though they may result in some weirdness, like have negative counts when a Poisson distributed outcome is forced to be normally symmetric. You could argue that the easy availability of powerful computers and tools like R make approximations unnecessary. For example, binom.test(), returns the exact results for a dichotomous outcome using the binomial formula, ( binom{n}{k} p^k q^{n-k})

Still approximations are quite popular and powerful, and you will find them in many epidemiology calculations. One common instance is the normal approximation to confidence intervals, ( mu pm 1.96 sigma) , where ( mu) is your point estimate, ( sigma) is the standard error of your measure, and ( pm 1.96) quantile values of a standard normal distribution density curve with area = 95% so that ( Pr[z leq −1.96] = Pr[z geq 1.96] = 0.025 )

Since the natural scale for a rate or a risk os bounded by zero (you can't have a negative rate) the approximation involves a log transformation, which converts the measure to a symmetric, unbounded more “normal” scale. (This is the same thinking behind logit transformations of odds ratios.)

The following code demonstrates the normal approximation to a confidence interval in action. It is taken from Tomas Aragon's “epitools” package, which in turn is based on Kenneth Rothman's description in “Modern Epidemiology”

the binomial distribution

The binomial model is probably the most commonly encountered probability distribution in epidemiology, and most epidemiologists should be at least moderately familiar with it. The probability that an event occurs (k) times in (n) trials is described by the formula (binom{n}{k} p^k q^{n-k}) where (p) is the probability of the event occurring in a single trial, (q) is the probability of the event not occurring ((1-p)) and (binom{n}{k}) is the binomial expansion “n choose k” the formula for which is ( frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!})

We'll use the concept of an LD50 to demonstrate a binomial model. An LD50 is the dose of a drug that kills 50% of a population, and (clearly) an important pharmacologic property. In his book “Bayesian Computation with R” Jim Albert applies it to a population with an increased risk of blindness with increasing age. We want to fit a logistic model in R to estimate the age at which the chance of blindness is 50%.

(y) is number blind at age (x) and (n) is the number tested

y has form ( y sim B(n, F(beta_0 + beta_1x))

where ( F(z) = e^z / (1+e^z)) ,i.e. logit, and

LD50 = ( frac{-beta}{beta_1}) i.e. point at which argument of the distribution function is zero

The data are:

Age: 20 35 45 55 70

No. tested: 50 50 50 50 50

No. blind: 6 17 26 37 44

We begin by reading the data into R

There are a couple of approaches to these data:

response is a vector of 0/1 binary data

response is a two-column matrix, with first column the number of

success for the trial, and the second the number of failuresresponse is a factor with first level (0) failure, and all other

levels (1) success

We'll use the second approach by adding a matrix to the data frame

And then fit a binomial model using glm()

The response variable is the number of people who become blind out of the number tested. Age is the predictor variable. Logit is the default for the R binomial family, but you could specify a probit model with family=binomial(link=probit)

To summarize our results:

the Poisson distribution

After the normal and binomial distribution, the most important and commonly encountered probability distribution in epidemiology is the Poisson. The Poisson distribution is often referred to as the “distribution of rare events”, and (thankfully) most epidemiologic outcomes are rare. It is also the distribution for count data, and epidemiologists are nothing if not counters.

The Poisson, gamma and exponential distributions are related. Counts on a timeline tend to be Poisson distributed, ( Pr[k]= e^{-lambda} * lambda^{k} /k! ). The time periods between the counts, tend to be exponentially distributed, with a single parameter, ( lambda = rate = mu = sigma^{2}). The exponential distribution in turn is a instance of a gamma distribution.

Gamma distributions are defined as the sum of k independent exponentially distributed random variables with two parameters: a scale parameter, ( theta) , and a shape parameter, ( kappa). The mean for a gamma distribution is ( mu=theta kappa). The shape parameter ( kappa) is the number of sub-states in the outcome of interest. In an exponential distribution there is a single transition state and you are counting every observation, so ( kappa =1). If you were interested in some process where you counted every other observation on a timeline, for example if there is some incubation period, you could model it with a ( thicksim Gamma(lambda, 2))

Because we do as epidemiologists spend a lot of time counting disease occurrences, you can get a lot of epidemiologic mileage from a Poisson distribution. R makes working with Poisson distributed data fairly straightforward. Use dpois() to return the density function (( Pr[X=x] = frac{x^{−lambda} lambda^{x}}{x!}) , where ( X =rv), (x) is the observed count, and ( lambda) is the expected count) is. Use ppois() to return the CDG (( Pr[X leq x] = sum_{k=0}^ x frac{k^{−lambda} lambda^{k}}{k!})).

Here is an example (shamelessly taken from Tomas Aragon, as are many other examples and material I use) of the Poisson distribution in action. Consider meningococcal disease. The US rate of meningococcal disease is about 1 case per 100,000 population per year. In San Francisco with a population of 800,000, we would expect 8 cases per year. What is the probability of observing exactly 6 cases? What is the probability of observing more than 10 cases?

the Poisson model

To get a better sense of the Poisson model consider horse kicks in the 19th century Prussian cavalry. No really. Simeon Denis Poisson was a student of Laplace in the 18th century who was interested in the application of probability in law enforcement and justice. He came up with a special case of the Gaussian distribution when the probability of an outcome is very small and the number of possible trials is very large: ( Pr[k]= frac{lambda^k}{k!} e^{-lambda}) , where ( mu = sigma^2 = lambda) . He would ask questions like, “If we usually see two murders a week, how unusual is it to observe 4?”

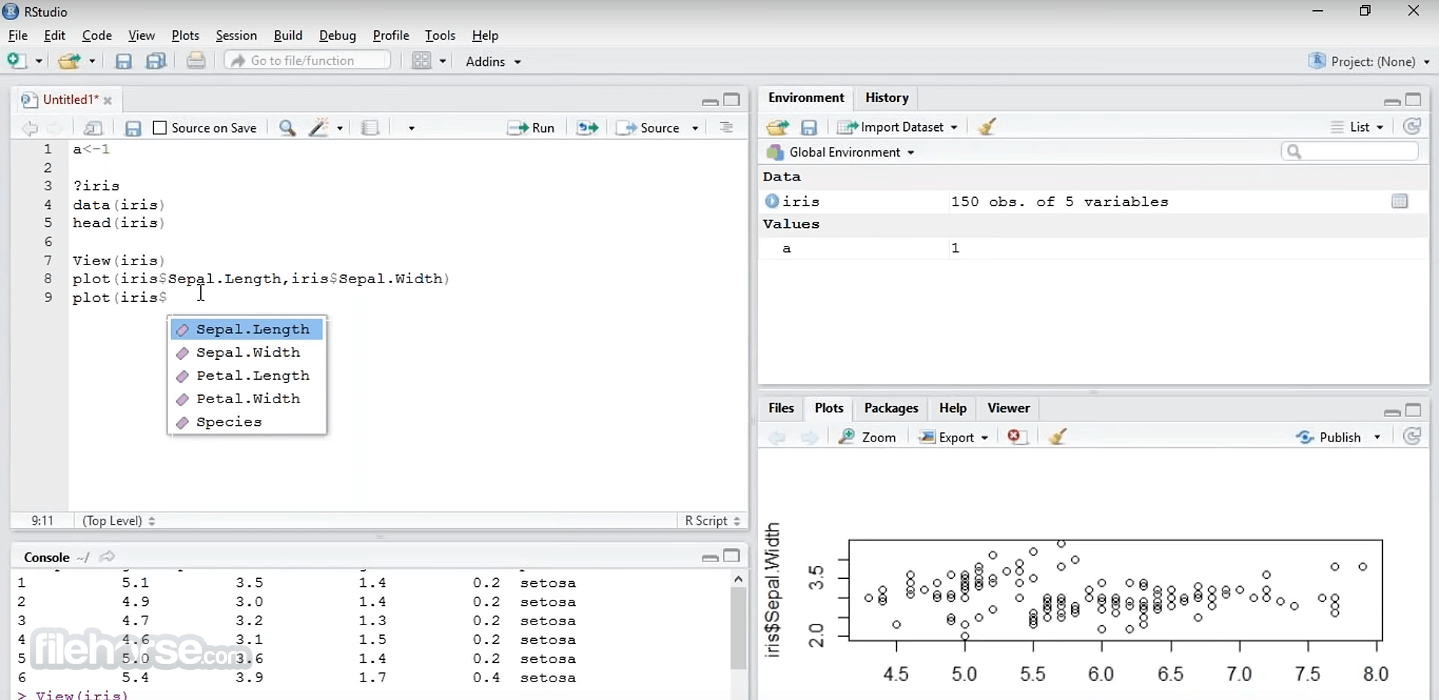

R Studio 10.5.8 Full

Fast forward to Ladislaus Bortkiewicz, a Polish mathematician who in his 1898 book “The Law of Small Numbers” applied the Poisson distribution to an early and unique injury epidemiology question: horse kick injuries in the Prussian army. He observed a total of 196 horse kick deaths over 20 years (1875-1895). The observation period consisted of 14 troops over 20 years for a total of 280 troop-years of data, so the underlying rate was ( lambda = 196/280 = 0.7) He then compared the observed number of deaths in a year to that predicted by Poisson. For example, the probability of a single death in a year is predicted as:

( Pr[1]=e^{-.7}*.7^1/1!=0.3476)

( 0.3476*280=97.3) or approximately 97 deaths

Here are his results for the actual, vs the predicted number of deaths:

| number of deaths | observed | predicted |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 144 | 139 |

| 1 | 91 | 97.3 |

| 2 | 32 | 34.1 |

| 3 | 11 | 8.0 |

| 4 | 2 | 1.4 |

| 5 or more | 0 | 0.2 |

And here is a quick R function for making these kinds of calculations.

normal approximation to confidence intervals for Poisson data

The Poisson distribution can also be used for rates by including a so-called “offset” variable, which divide the outcome data by a population number or (better) person-years (py)of observation, which is considered fixed. We can use a normal approximation to calculate a confidence interval, where

( sigma_{r} = sqrt{x/py^2})

( r_{L}; r_{U} = r pm z × sigma_{r})

For example say we observe 8 cases of cancer over 85,000 person-years of observation. Out rate is 9.4 cases / 100,000 p-yrs. The following code returns a 90% confidence interval:

You can generalize this into a function:

exact approximation to confidence intervals for Poisson

For very small counts, you may want to consider an exact approximation rather than a normal approximation because your data may be less symmetric than assumed by the normal approximation method. Aragon describes Byar’s method, where

- (r_L, r_U = (x+0.5) left (1-frac{1}{9(x+0.5)} pm frac{z}{3} sqrt{frac{1}{x+0.5}} right )^3 / person-years)

A 90% CI for 3 cases observed over 2,500 person-years (12/10,000 p-y) would be coded as:

exact tail method for Poisson data

You can (again with code from Tomas Aragon) use the uniroot() function to calculate the exact Poisson confidence interval from the tails of the distribution.

You can, alternatively use the the Daley method with the Gamma distribution

about p values

I'm not a big fan of them, but no discussion of probability in epidemiology would be complete without a consideration of p values. I'll try to remain agnostic.

A p value is the probability, given the null hypothesis, of observing a result as or more extreme than that seen. Assuming we know the underlying distribution from which the data arose, we can ask “How compatible is the value we observed to our reference value?” Consider a clinical scenario, where

- The proportion patients with some complication is (hat{r})

- The the proportion of such outcomes we consider the upper acceptable limit is (r_{0})

We are interested in whether some observed proportion is compatible with that acceptable limit.

- (H_{0}: hat{r} = r_{0})

- (p = Pr[r geq hat{r} | r = r_{0}])

We can use a p value to assess the probability (p) of observing a value of (hat{r}) as or more extreme than expected under the null hypothesis. The underlying assumption is that more extreme values of (hat{r}) unlikely to occur by chance or random error alone, and a low p value indicates that our observed measure is less compatible with the null hypothesis. Though, as most folks know, p values are sensitive to issues of sample size and need to be interpreted carefully.

Let's put some numbers on this. Is 8 complications out of 160 hospital admissions (5%) compatible with a goal or reference value of 3% or less? Assuming a binomial distribution, we can use the binom.test() to calculate a one-sided p value (because we are only interested in more complications), where

- n = 160 and k = 8 (binomial)

- (hat{r} = 8/160 = 0.05, r_{0} = 0.03)

- (p = Pr[r geq hat{r}=.05 | r_{0}=.03])

There is an 11% probability of observing 8 or more complications in 160 admissions. So, is a hospital complication risk of 5% compatible with a reference value (“goal”) of 3% or less? Or to use the common terminology, is this result statistically “significant”? The answer, as is so often the case, is “It depends.” In this case, I think you can make the argument that the 8 complications could have been due to chance. But, our p value depends on

the magnitude of the difference (5% vs 3%)

the number of observations or hospitalizations (sample size= 160)

The influence of sample size is considerable. Here are the (same) calculations for a 5% complication rate changing the number of hospitalizations i.e the sample size.

| (n) | (x) | p |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 1 | 0.4562 |

| 40 | 2 | 0.3385 |

| 80 | 4 | 0.2193 |

| 160 | 8 | 0.1101 |

| 640 | 32 | 0.0041 |

This is something worth keeping in mind whenever evaluating p values. The same concepts apply to common epidemiological measures like rate, risk and odds ratios, where the reference or null value is 1.

Kenneth Rothman has written extensively on the pitfalls of p values in epidemiology. One recommendation he has made is plotting a “p-value function” of two-sided p values for a sequence of alternative hypotheses. A p-value function gives a lot of information:

the point estimate

the confidence interval for the estimate

how likely or precise each value is

If you were to look for a p-value function plot in some of the more popular statistical packages your search would likely be in vain. This is where a programming language like R comes into its own. You can program it yourself or (perhaps) someone already has. In this case Tomas Aragon (yet again) took on himself to write up R code for a p-value function.

The function uses fisher.test() to returns a two-sided p value for count data in a 2x2 table. The Fisher exact test is based on a hypergeometric distribution modeling the change in the a cell. We will feed a range of odds ratio values to fisher.test().

Sampling and simulations are closely related to probability, so this is as good a place as any to talk about R's capabilities in this regard. Computing power makes simulations an attractive option for conducting analysis. Simulations and sampling are also a handy way to create toy data sets to submit to online help sites like StackOverflow.

sampling

Sampling using sample() is the most immediate and perhaps intuitive application of probability in R. You basically draw a simple random permutation from a specified collection of elements. Think of it in terms of tossing coins or rollin dice. Here, for example, you are essentially tossing 8 coins (or one coin 8 times).

Note the following options:

replace=TRUE to over ride the default sample without replacement

prob= to sample elements with different probabilities, e.g. over

sample based on some factorthe set.seed() function allow you to make a reproducible set of random numbers.

sampling from a probability distribution

Moving up to the next level of control, you can draw a set of numbers from a probability distribution using the rxxxx() family of functions.

When you're sampling from probability distributions other than the standard normal, you have to specify the parameters that define that distribution. For the binomial distribution, you specify the the number of replicates (n), the size or the number of trials in each replicate (size), and the probability of the outcome under study in any trial (prob). So, to specify 10 replicates of 20 trials, each with a 40% chance of success might return the following vector of the number of successes in each replicate, you might write:

might return

bootstrapping

Bootstrapping is type of sampling where the underlying probability distribution is either unknown or intractable. You can think of it as a way to assess the role fo chance when there is no simple answer. You use observed data to calculate (say) rates, and then apply those rates to a simulated population created using one of R's probability distribution functions, like (say) rbinom().

We'll demonstrate the process with a function that calculates a risk ratio estimate. The steps involve:

Create a simulated exposed sample (n_1) by of 5000 replicate bernoulli trials with a probability parameter defined by the observed risk of x1/n1.

Divide (n_1) by the total sample size to get 5000 simulated risk estimates for the exposed group.

Repeat the process for the unexposed group (n_2) to get a rate for the unexposed group.

Calculate the mean and 0.25 tails for the simulated populations.

the relative risk bootstrap function

plotting probability curves

You may, on some occasion, want to plot a curve or probability distribution. Here are a couple of approaches to plotting a standard normal curve but, they can be used for other probability distributions. The first comes from Tomas Aragon, the second from John Fox.

using the sequence operator

This approach uses the normal probability formula…

( f(x) = frac{1}{sqrt{2pi sigma^2}} left(exp frac{-left(x-muright)^2}{2sigma^2} right))

… over a sequence of values.

another approach

Here, we use the dnorm() function and add a few bells and whistles.

Contents

Here we look at some examples of calculating p values. The examplesare for both normal and t distributions. We assume that you can enterdata and know the commands associated with basic probability. We firstshow how to do the calculations the hard way and show how to do thecalculations. The last method makes use of the t.test command anddemonstrates an easier way to calculate a p value.

We look at the steps necessary to calculate the p value for aparticular test. In the interest of simplicity we only look at a twosided test, and we focus on one example. Here we want to show that themean is not close to a fixed value, a.

The p value is calculated for a particular sample mean. Here we assumethat we obtained a sample mean, x and want to find its p value. It isthe probability that we would obtain a given sample mean that isgreater than the absolute value of its Z-score or less than thenegative of the absolute value of its Z-score.

For the special case of a normal distribution we also need thestandard deviation. We will assume that we are given the standarddeviation and call it s. The calculation for the p value can be donein several of ways. We will look at two ways here. The first way is toconvert the sample means to their associated Z-score. The other way isto simply specify the standard deviation and let the computer do theconversion. At first glance it may seem like a no brainer, and weshould just use the second method. Unfortunately, when using thet-distribution we need to convert to the t-score, so it is a good ideato know both ways.

We first look at how to calculate the p value using the Z-score. TheZ-score is found by assuming that the null hypothesis is true,subtracting the assumed mean, and dividing by the theoretical standarddeviation. Once the Z-score is found the probability that the valuecould be less the Z-score is found using the pnorm command.

R Studio 10.5.8 Crack

This is not enough to get the p value. If the Z-score that is found ispositive then we need to take one minus the associatedprobability. Also, for a two sided test we need to multiply the resultby two. Here we avoid these issues and insure that the Z-score isnegative by taking the negative of the absolute value.

We now look at a specific example. In the example below we will use avalue of a of 5, a standard deviation of 2, and a sample sizeof 20. We then find the p value for a sample mean of 7:

We now look at the same problem only specifying the mean and standarddeviation within the pnorm command. Note that for this case we cannotso easily force the use of the left tail. Since the sample mean ismore than the assumed mean we have to take two times one minus theprobability:

Finding the p value using a t distribution is very similar to usingthe Z-score as demonstrated above. The only difference is that youhave to specify the number of degrees of freedom. Here we look at thesame example as above but use the t distribution instead:

We now look at an example where we have a univariate data set and wantto find the p value. In this example we use one of the data sets givenin the data input chapter. We use the w1.dat data set:

Here we use a two sided hypothesis test,

So we calculate the sample mean and sample standard deviation in orderto calculate the p value:

Suppose that you want to find the p values for many tests. This is acommon task and most software packages will allow you to do this. Herewe see how it can be done in R.

Here we assume that we want to do a one-sided hypothesis test for anumber of comparisons. In particular we will look at three hypothesistests. All are of the following form:

We have three different sets of comparisons to make:

| Comparison | 1 | ||

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Number(pop.) | |

| Group I | 10 | 3 | 300 |

| Group II | 10.5 | 2.5 | 230 |

| Comparison | 2 | ||

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Number(pop.) | |

| Group I | 12 | 4 | 210 |

| Group II | 13 | 5.3 | 340 |

| Comparison | 3 | ||

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Number(pop.) | |

| Group I | 30 | 4.5 | 420 |

| Group II | 28.5 | 3 | 400 |

For each of these comparisons we want to calculate a p value. For eachcomparison there are two groups. We will refer to group one as thegroup whose results are in the first row of each comparison above. Wewill refer to group two as the group whose results are in the secondrow of each comparison above. Before we can do that we must firstcompute a standard error and a t-score. We will find general formulaewhich is necessary in order to do all three calculations at once.

We assume that the means for the first group are defined in a variablecalled m1. The means for the second group are defined in a variablecalled m2. The standard deviations for the first group are in avariable called sd1. The standard deviations for the second group arein a variable called sd2. The number of samples for the first groupare in a variable called num1. Finally, the number of samples for thesecond group are in a variable called num2.

With these definitions the standard error is the square root of(sd1^2)/num1+(sd2^2)/num2. The associated t-score is m1 minus m2all divided by the standard error. The R comands to do this can befound below:

To see the values just type in the variable name on a line alone:

To use the pt command we need to specify the number of degrees offreedom. This can be done using the pmin command. Note that there isalso a command called min, but it does not work the same way. Youneed to use pmin to get the correct results. The numbers of degreesof freedom are pmin(num1,num2)-1. So the p values can be foundusing the following R command:

If you enter all of these commands into R you should have noticed thatthe last p value is not correct. The pt command gives the probabilitythat a score is less that the specified t. The t-score for the lastentry is positive, and we want the probability that a t-score isbigger. One way around this is to make sure that all of the t-scoresare negative. You can do this by taking the negative of the absolutevalue of the t-scores:

The results from the command above should give you the p values for aone-sided test. It is left as an exercise how to find the p values fora two-sided test.

The methods above demonstrate how to calculate the p values directlymaking use of the standard formulae. There is another, more direct wayto do this using the t.test command. The t.test command takes adata set for an argument, and the default operation is to perform atwo sided hypothesis test.

That was an obvious result. If you want to test against adifferent assumed mean then you can use the mu argument:

If you are interested in a one sided test then you can specify whichtest to employ using the alternative option:

R Studio Download For Windows

The t.test() command also accepts a second data set to compare twosets of samples. The default is to treat them as independent sets, butthere is an option to treat them as dependent data sets. (Enterhelp(t.test) for more information.) To test two different samples,the first two arguments should be the data sets to compare: